The Problem with Magic

Why "Human in the Loop" Isn't Enough

When a patient asks how their belongings get to the recovery room, I usually tell them, “Magic!”

Similar to a small child who thinks their food magically appears without realizing all the effort parents put into buying, cooking, and cleaning up meals, I have no idea who picks up the clear bags of patient clothes with eyeglasses lovingly tucked into their shoes and puts them in a different part of the hospital. I’ve been practicing for 20 years, so you’d think I’d have seen someone do this at some point. But no. As far as I’m concerned, there’s a magic conveyor belt whisking these bundles to the right spot. Somewhere between pre-op and post-op, a patient’s clothes, wallet, and phone travel through the hospital and arrive exactly where they need to be. I’ve seen it happen hundreds of times but I have no idea who does it, what triggers it, or how anyone ensures nothing gets lost.

In short, it’s magic.

By magic, I mean knowing that a task happens but having absolutely no idea what the mechanics are, who does it, what triggers it, what the quality assurance looks like.

This seemingly innocuous blind spot reveals something critical about how healthcare actually works, and why that matters when we start adding AI into the mix.

Magic is everywhere

My reliance on magic is vaguely embarrassing, since I’ve spent decades working on clinical workflow, developing clinical initiatives, and reviewing patient safety events. But when I started asking colleagues, I discovered I wasn’t alone. Most clinicians have their own version of “magic” processes, which they know happen but can’t explain exactly how. Employed physicians sometimes think billing is magic. Physicians almost universally think the steps between a patient’s diet order and the food that appears at bedside is magic. Occasionally the magic actually feels magical, like when a therapy dog arrives at the bedside of a crying pediatric patient.

This isn’t ignorance. No one can hold every process in their head, so we trust that the pieces we don’t understand are being handled by someone who does. And historically, that trust has been reasonable. The magic works because humans are embedded throughout the system to catch errors, improvise in non-standard situations, and escalate when something feels wrong.

The magic works because someone, in some part of the system, knows what they’re responsible for.

But what happens when we start automating the magic?

Automating What We Don’t Understand

AI vendors are increasingly promising to automate hospital tasks like intake, scheduling, and patient screening. These promises are appealing because the tasks are real, often repetitive, and the inefficiencies are frustrating.

The problem is that many of these tasks were never fully mapped in the first place. When a pre-visit chatbot starts gathering patient history, we’re automating something a human used to do, but do we know everything that humans were actually catching along the way? When an AI suggests medication dosing instead of the pharmacist, the nurse and physician all might assume the pharmacist is still responsible for and checking the output. If we automate processes we never fully understood, we’re creating new handoffs that nobody knows exist.

This matters because most healthcare errors aren’t dramatic failures of technology or competence, but communication breakdowns like handoff failures or assumptions about the actions of others. We already struggle with visible handoffs, and now we’re creating invisible (magic!) handoffs. We’ve come a long way from when I carried around printed pages of the patient census with notes for each patient scribbled in the margins, but at least I knew I was responsible for those 90 floor patients overnight. Now clinicians might have AI tools performing “magic” but be responsible for the results.

The Problem of Distributed Responsibility

There’s a term for what’s happening here: distributed responsibility. This is when accountability for a task or outcome is spread across multiple actors, whether human and/or AI, without clear delineation of who is responsible for what specific aspect.

With AI, we’re distributing responsibility without mapping it. The AI screens the patient, but who owns the screening decision? The AI suggests a dose, but who is accountable for verifying it’s appropriate for this specific patient? The AI flags a risk, but who is responsible for acting on it, or for recognizing when the flag is wrong?

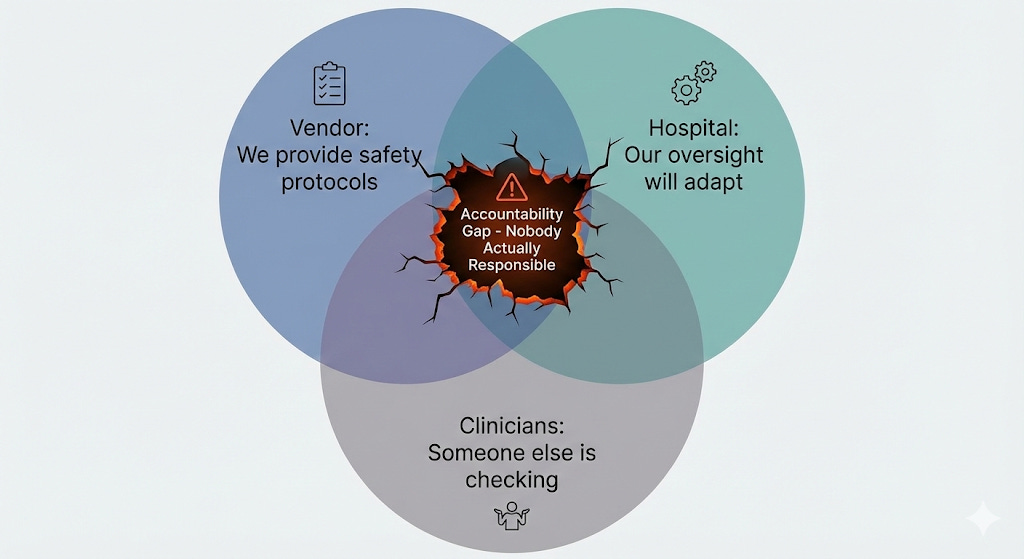

This creates accountability gaps, when everyone assumes someone else is checking the AI’s work, and therefore no one actually is. It’s distributed responsibility without distributed awareness. I consider this a structural risk: not a problem with the technology itself, but with how AI integration creates systemic vulnerabilities in accountability and oversight. These gaps persist even when the AI performs perfectly, because they’re fundamentally about how we’ve organized human responsibility around automated processes we never fully mapped.

The danger isn’t just that things might fall through the cracks. It’s that when they do, no one will be there to catch them.

Where is the incentive?

It’s worth asking who would benefit from making this chain of responsibility more clear.

Vendors have little incentive to map out distributed responsibility in detail, both because each client may have a different process, and because getting too involved might lead to more questions about their liability. Hospitals, meanwhile, might unconsciously prefer ambiguity because it enables faster implementation. Mapping every handoff, training every user, and redesigning workflows to accommodate new AI tools takes time and resources. It’s much faster to assume existing oversight will naturally adapt. By the time someone realizes the adaptation didn’t happen, the tool is already embedded in daily operations, and the question becomes “how do we make this work?” rather than “should we have done this differently?”

Right now, neither FDA nor CMS requires vendors to map out distributed responsibility in their AI tools. FDA’s guidance focuses on the algorithm’s technical performance like accuracy, validation datasets, bias metrics. But it doesn’t ask: ‘Who in the clinical workflow is responsible for catching this algorithm’s specific failure modes? How have you ensured they know that’s their job?’ CMS’s AI frameworks ask about governance structures but don’t require documentation of who is responsible for catching what failures at which points in the workflow. The result is that a tool can pass regulatory review while creating significant accountability gaps in practice.

The result is a tacit agreement to not look too closely at who is responsible for what. Everyone can claim they’re being careful, vendors point to safety protocols, hospitals point to clinical oversight, while the clinicians and staff try to plug the gaps in between.

The “Human in the Loop” Illusion

Every AI safety protocol I’ve seen includes some version of “there’s a human in the loop.” And this makes sense, because in many ways we already have a system that relies heavily on a human - an attending physician - in the loop, so it’s a familiar role.

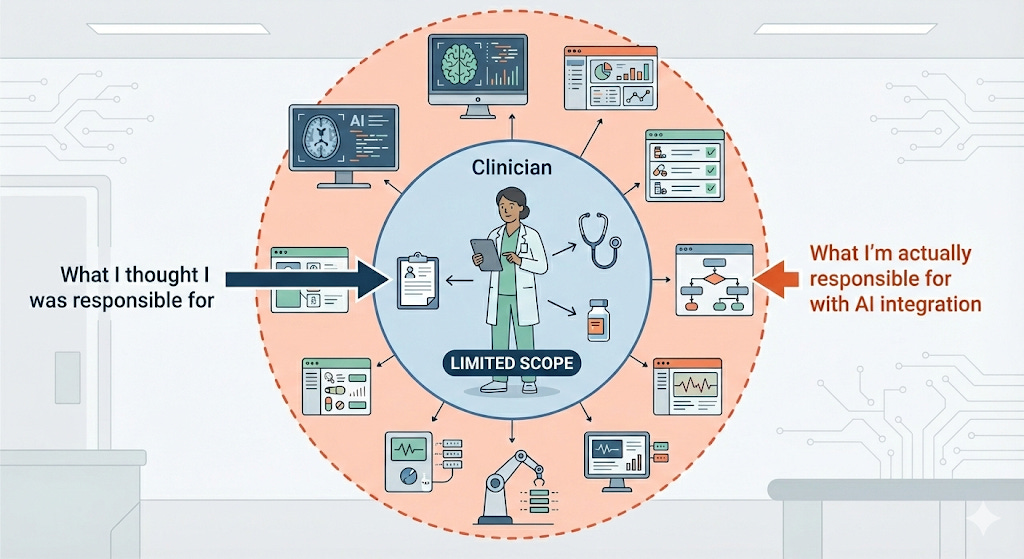

But what if that human doesn’t realize they’re now responsible for everything a human used to do and catch?

Consider a scenario: An AI tool pre-screens patients before a physician visit, flagging some for follow-up and routing others to standard care. The physician sees patients on the standard pathway without knowing an AI made the initial triage decision. Technically, there’s a human in the loop, since the physician is seeing the patient and making clinical decisions. But the physician doesn’t know they’re also supposed to be catching whatever the AI might have missed upstream. That was previously handled by an experienced nurse, who has now been taken out of the process. The doctor is now in a bigger loop than they’re used to, with more area for them to cover.

Or consider a tool that assists with medication dosing. Traditionally: the physician orders, the pharmacist verifies, the nurse administers. Everyone knows their role.

Now add an AI that checks dosing before administration. The tool gets rolled out to pharmacy and nursing. The pharmacist assumes the physician knows about the AI and is ordering with that in mind. The nurse assumes both the pharmacist and the AI have verified the dose. And the physician? They might have no idea the tool exists. They’re still assuming the pharmacist is doing their usual verification, not realizing that the pharmacist’s role has shifted and they’re now more responsible for the initial order being correct.

Technically, there’s a human in the loop—the physician is still ordering. But the physician doesn’t know they’re now in a bigger loop, responsible for catching what the AI or the pharmacist with new workflows might miss.”

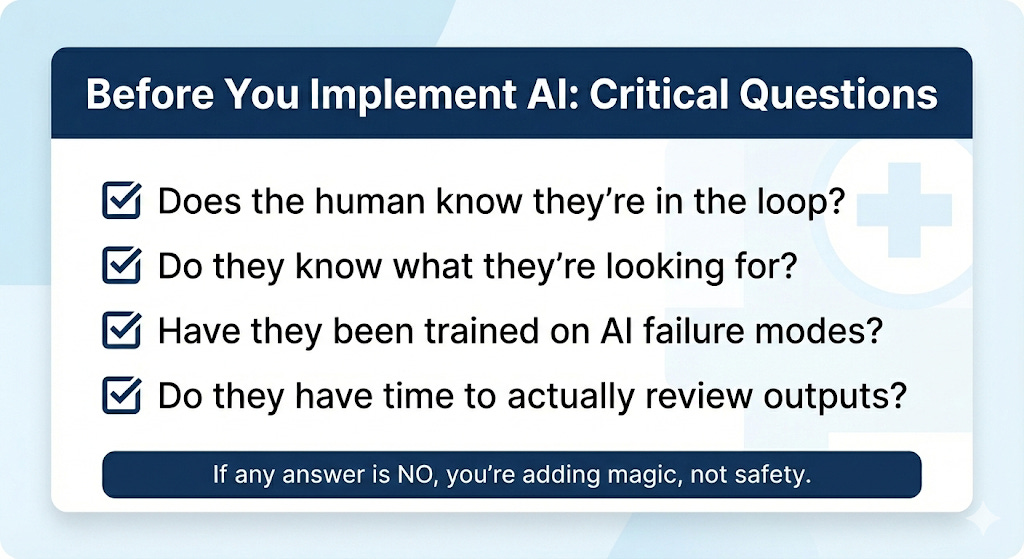

The question we should be asking is specific: *What is this human supposed to do? Are there AI inputs or outputs they should be reviewing? Do they know that’s their job? Have they been trained to do it?*

You can’t catch what you don’t know you’re supposed to be looking for.

What We Can Do

None of this means we shouldn’t implement AI in healthcare, or even that AI is intrinsically higher-risk than other healthcare workflows. It just means we need to do the boring work before we do the exciting work (boring for normal people, I actually think workflow mapping is really fun):

Map the magic before you automate it. Before implementing any AI tool, document what currently happens. Who does this task now? What do they catch along the way? What’s the quality assurance? If you can’t answer these questions, you’re not ready to automate.

Make responsibility explicit, not assumed. “Who is responsible if this fails?” should have a name attached—a specific person who knows it’s their job and has been trained to do it. “Human in the loop” is not a name. It’s a hope.

Train the humans on what they’re actually in the loop for. If a physician is supposed to catch AI triage errors, they need to know the AI exists, understand its failure modes, and have a workflow that supports meaningful review. Oversight without awareness isn’t oversight.

This work isn’t glamorous, and workflow documentation doesn’t make for exciting press releases or investor pitches. But it’s the difference between AI that genuinely improves care and AI that creates new, invisible ways for things to go wrong.

The Magician Has to Know They’re the Magician

Healthcare has always run on a certain amount of magic—processes too complex for any one person to fully understand. That’s fine, as long as responsibility is clearly defined. The system works because people know what they’re supposed to catch, even if they don’t know what everyone else is doing.

AI changes the equation by automating tasks we never fully mapped and creating handoffs we never named. “Human in the loop” can’t be a checkbox on a safety protocol. It has to be a job description, with specific training, specific accountability, and specific workflows that make oversight actually possible.

The next time someone tells you an AI tool is safe because there’s a “human in the loop,” ask them: Does that human know they’re in the loop? Do they know what they’re supposed to be looking for? Have they been trained on the AI’s failure modes? Do they have time to actually review the AI’s outputs, or are they just clicking through?

If the answer to any of these questions is no, you’re not adding safety. You’re adding magic. And eventually, someone’s going to get hurt trying to figure out how the trick was done.

I work with companies and investors on evaluation, governance, and clinical integrity. You can reach me through Validara Health or by email sarah (at) validarahealth.com.

These are helpful recommendations in the context of AI, but I can't help but think that you could remove every reference to AI from this post and the advice would be just as relevant. Process mapping, explicit ownership, training—these are the foundations of any successful business, and they're frequently missing in healthcare. And rather than do that important but unglamorous work, I think many healthcare organizations would rather just use AI as a way to throw more, cheaper "bodies" at the problem.

This is reminiscent of but possibly worse than the decades old stories of EHR implementation when we spoke of the inappropriateness of "paving the cowpaths" instead of designing better workflows. But at least we knew exactly the paths that the cows were on?