I was sitting in a med school study room, taking a break from looking at pathology slides, when my friend suggested signing up for a new way to talk to your friends from other schools. A minute later, I had one of the first Facebook accounts in the country, connected to my @stanford.edu email. It was the early 2000s. Friends was in its final season. The Office had just premiered. I was downloading music on LimeWire and wearing low-rise jeans.

That same year, the Witty worm had just torn through the internet, the latest in a series of worm attacks that infected thousands of computers within minutes. Suddenly, companies had to confront a truth we now take for granted: software isn’t trustworthy just because it works.

As an expert said in 2004, the “lesson is that the patching model for fixing security problems just isn't working.” In other words, reactive responses didn’t cut it anymore. They realized they needed a more proactive approach.

In the world of cybersecurity, that moment catalyzed an entire field. Structured, proactive validation like penetration testing as a service, red teaming, and frameworks like SOC 2 and PCI-DSS were developed around that time. Security shifted from an afterthought to an expectation—something you built in from the start, not hoped for at the end. We trust software in our banking systems because its edges and flaws have been tested, monitored, and risks have been mitigated. We realize those interventions don’t lead to perfection, but that it will be better and more trustworthy than it would be without it.

Healthcare AI is now wrestling with its own version of that realization: our current method for evaluating healthcare AI products just isn’t working.

The foundational medical virtues of first do no harm and provide the best care for each patient are the lodestars for what we want from our healthcare AI products. And yet we can’t say with certainty that many of the healthcare AI tools are accomplishing those crucial goals. If we want AI to have a place in healthcare, we have to demonstrate that it can uphold the values of medicine.

From Cold War to Code Red: How Cybersecurity Became a Field

Cybersecurity started in the 1970s and 1980s, as the U.S. military began using networked computers. The Department of Defense formed “Tiger Teams” to simulate intrusions and test system vulnerabilities. These were the original red teamers, hired to think like adversaries and break what wasn’t supposed to break.

In 1983, the term “computer virus” was introduced by a researcher whose doctoral student pestered him for permission to create a program that would gain control of a computer. By 1986, Congress passed the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) after a wave of amateur hacks (including a group of teenagers known as The 414s, who hacked into Los Alamos National Laboratory and Memorial Sloan Kettering) revealed just how vulnerable U.S. systems really were. But despite these early warnings, most businesses didn’t take cybersecurity seriously until it affected revenue, both from a direct loss of profit and from sales challenges without cyber protections in place (a huge surprise, I know).

Security Frameworks Were Developed by…Accountants?

As the internet became essential to selling us iPods and Tamagotchis, compliance began to catch up. Key players emerged to standardize how companies should secure themselves:

The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) developed the SOC (System and Organization Controls) frameworks to provide third-party assurance for organizations handling sensitive data.

SOC 1 (early 2000s) focused on financial controls.

SOC 2, introduced in 2011, expanded to include security, availability, processing integrity, confidentiality, and privacy—what we now consider the core pillars of data trust.

SOC 2 wasn’t a government mandate; it was market-driven. Vendors wanted to sell to companies, and companies wanted proof of risk management.

The PCI Security Standards Council (founded in 2006 by major credit card companies) created PCI-DSS—a formal requirement for companies handling credit card data to undergo regular security testing, including penetration testing.

ISO/IEC 27001, originally developed in the UK in the 1990s and formalized internationally in the early 2000s, gave global companies a blueprint for building an information security management system.

https://secureframe.com/hub/soc-2/history

Why accountants? Because in the 1970s accountants developed standards to “determine how effective a company’s internal financial controls were,” which expanded to general information security by the early 1990s.

By the late 2000s, testing evolved from “Tiger Teams” first deployed to find military software flaws to penetration testing approaches that were scalable, repeatable, and integrated into development cycles. And most importantly, it became an expectation in the industry, because you can’t sell a product—or defend it—without it.

Penetration testing became normalized not because it fulfilled some lofty ideal, but because it was a way to prove security in a standardized, auditable way. Trust shifted from vague assurances to shared expectations.

Healthcare AI is Where Cybersecurity was in the Early 2000s

Healthcare AI is now powering diagnostic tools, treatment recommendations, and triage pathways, but without the equivalent of SOC 2, PCI-DSS, or ISO 27001. Like cybersecurity in the early 2000s, we have:

Known vulnerabilities (bias, drift, misuse)

Tools to identify them (real-world testing, human baselining)

No requirement, or even consensus, on how to do that well

There’s no standard for what good validation looks like, no clear roles for third-party testing, and no shared expectations for liability. There is very little stress-testing, red-teaming, or ongoing monitoring.

We’re not just missing the tests. We’re missing the trust architecture.

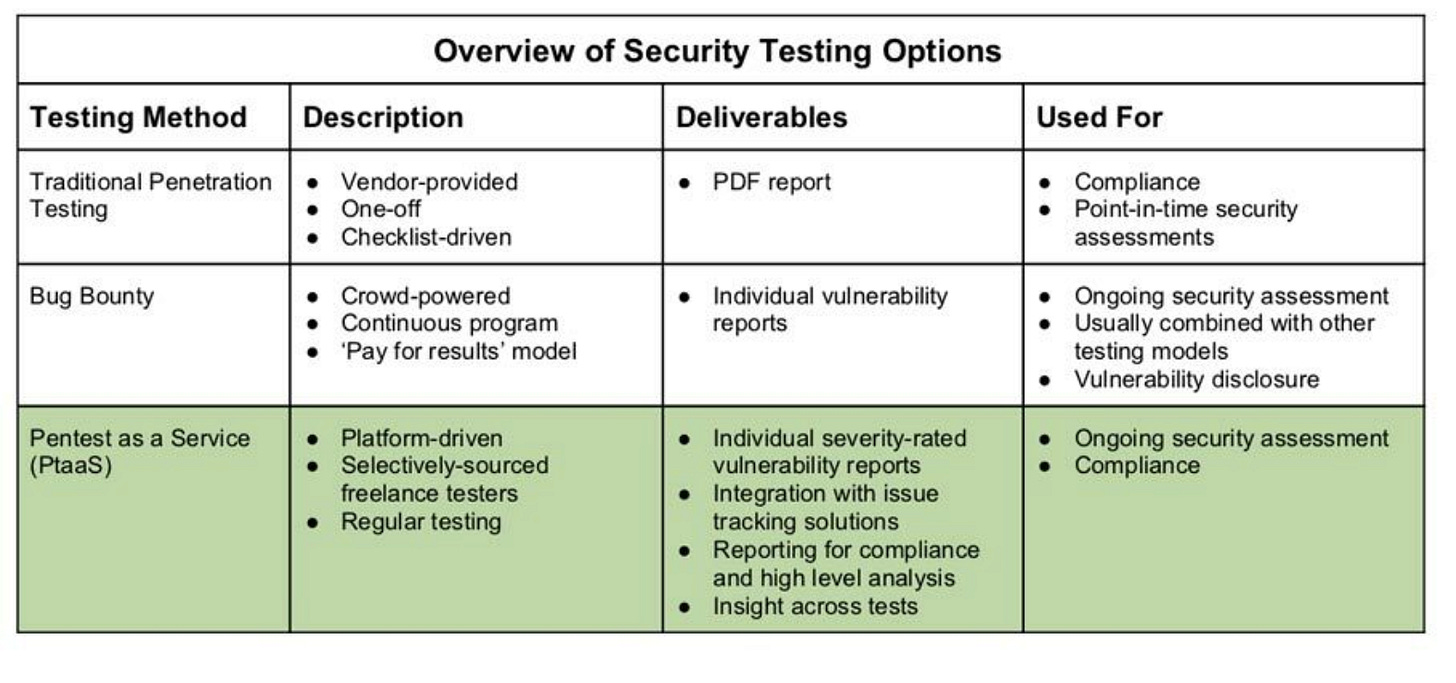

Here’s what structured AI validation could look like, borrowing directly from the cybersecurity playbook:

In short, we don’t just need to know that an AI works in theory. We need to know how it performs in practice, in the bizarre situations clinicians sometimes find themselves in, and in different environments.

We Can’t Wait Another 20 Years

It took decades for cybersecurity to mature into a lifecycle discipline. The current system developed based more on market forces than regulations, and I expect that to be the same for healthcare AI.

We’re at that moment with AI now. But the system to ensure trust has to identify the tools that will improve patient lives without harming patients, or adoption will stall. Patients who could have benefited most will lose out.

Coming Soon: A Framework for Trust Architecture

That’s why we’re building the Trust by Design Framework, a new way to evaluate and validate healthcare AI that incorporates the best ideas from cybersecurity, systems engineering, and clinical safety science. And we’re adapting them to the messy, variable, high-stakes world of healthcare.

If you’re a vendor, investor, or healthcare leader trying to separate signal from noise in AI, this framework is for you. If you’ve ever wondered how do I know this works, and that I can trust it? Ultimately, will it uphold medicine’s ideals? we’re building the answer.

Stay tuned. We’ll be publishing a preview next month (but sign up here for early access)