The alarm started to beep as my patient’s blood pressure dropped to 84/50. I remember holding a vial of phenylephrine in my hand on my first day alone as an anesthesiology resident. I had never given the drug by myself before and I was mostly sure I was supposed to give 80mcg of the drug, but also not completely confident. So I looked up the side effects on my cheat sheet, then looked up how to dilute the vial. Then I had to find the right size syringe and label. By the time I finally drew up the right amount of medicine the patient’s blood pressure had recovered on its own.

Fast forward 15 years and I give that same medication all the time. The amount of thinking I have to do when I perform the same function is drastically lower. My cognitive load, or the work my brain has to do, to decide whether to give phenylephrine and draw it up has changed dramatically with years of practice.

I recently described the “highly interruptive river of healthcare” and firmly believe that the constant pull on physician attention is related to physician burnout. There’s good evidence for cognitive load theory (CLT), a concept that was first developed in the education field to assess how many new tasks or ideas a human could learn at a time.

CLT says that people get sensory inputs, which go into working memory and help put meaning to the sensory inputs, which then may be placed in long-term memory. We’re going to focus on that intermediate stage of working memory, which can process 5-9 chunks of information at a time. Working memory is where input, which can be any kind of information, is either thrown out or kept. Importantly, it does not seem possible to increase the capacity of working memory significantly.

Jobs with more intellectual and emotional complexity lead to a higher cognitive load, so it’s not surprising that physicians would have a high baseline cognitive load. One study notes that additions to cognitive load may be exponential rather than additive.

Other factors that affect cognitive load

Intrinsic load: How complicated or emotionally taxing the task is. This includes the “second (and third) victim” issue

Germane load: Our pre-existing skills at that task. If we’re already more skilled, it will be less of a cognitive load. This is very clear to people when they have their second baby for example, and they realize how much of their exhaustion was related to not knowing what to do with a newborn, whereas the second kid is more exhausting because you are dealing with the first kid. Or think of how much you had to think about writing admission orders as an intern vs as an attending.

Extraneous load: How much effort you have to expend to get and understand information necessary to complete the task. If you can just call a colleague and ask for a curbside consult, that is much less of a cognitive load than if it’s the middle of the night and you have to look up a rare syndrome and try to remind yourself of the critical details. This also has to do with how the information is presented. As we all know, listening to a senior resident or a colleague describe a patient is much less taxing than listening to a second-year medical student. The more senior people will give you the information you want in the format you expect it, so your brain doesn’t have to work as hard.

Personal plus professional

One important aspect of cognitive load is that your brain doesn’t distinguish between personal and professional cognitive loads. So if you kid is having a hard time and you’re also caring for a lot of sick patients in the ICU, those are in the same bucket, as much as you’d like to separate them. Accepting that the brain has a limited capacity to deal with tasks and emotional issues may make it feel more acceptable to physicians to step back from some kinds of clinical work when personal issues are particularly pressing.

Excess cognitive load as a precursor to burnout

One fascinating conclusion of a recent paper was that excess cognitive load, burnout, and depression all have similar symptoms: increased mistakes, difficulty completing previously mastered tasks, and deteriorating communication and interpersonal skills. While the relationship between burnout and depression have been extensively debated, the possibility of increased awareness of excess cognitive load as a precursor to burnout could lead to earlier intervention.

Metacognition, or awareness of attention, may help physicians identify when their cognitive load is being overburdened, and when their attention is being interrupted too often.

Context switching

A related concept is context switching, defined as when you stop a project before you get all the way through it and start something else instead. Context switching and interruptions also cause “a higher workload, more stress, higher frustration, more time pressure, and effort”. I’ve been paying more attention to the costs of my own context switching lately, and it’s amazing how much productivity I lose every time I’m distracted. I’m writing this at 4:23am for that exact reason: I know it will take me half the time if I can do it before my kids wake up and I start getting texts and emails. When you context switch, you lose 20% of your cognitive capacity and it takes more than 20 minutes to fully re-engage after you’re interrupted.

Context switching differs somewhat from multitasking (though some argue multitasking is just very rapid context switching), in which you try to do multiple different things at once, which is also not very effective. Just 2.5% of people are effective multitaskers, which I’m hesitant to even mention because my guess is that 95% of physicians will believe they fall into this category. What makes this statistic more misleading is the data that shows the least efficient multitaskers are those who are most likely to practice it.

How can AI help with cognitive load?

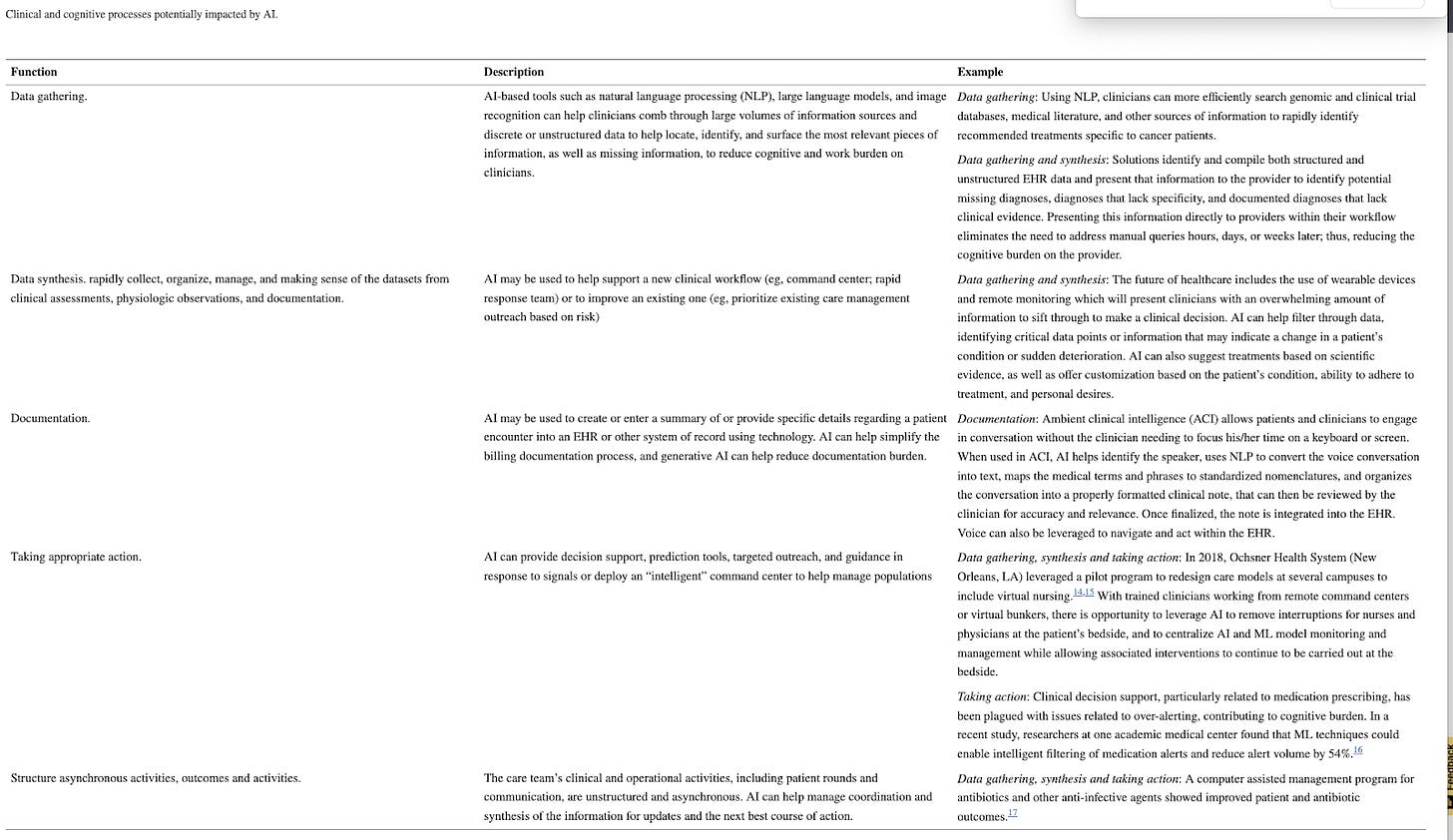

This paper mentions several kinds of tasks that can help decrease physician cognitive load:

Data gathering, like looking through charts and labs

Data synthesis, like writing the ‘history’ section for pre-charting before you see a patient

Documentation, like ambient scribes for note writing and putting in orders

Triage, by helping decide which tasks are most urgent

Coordination of care, by synthesizing information from all medical team members (my addition: also hopefully someday prompting you to remember to follow up with specialists or others for specific patients)

I’ll add several more:

Administrative calendar scheduling, so you can avoid emailing back and forth with people you need to meet with and also keep your family’s commitments straight

Idea generation, so you can brainstorm more quickly

Feedback on ideas or proposals, so you can move forward instead of keeping that idea in your working memory

Task managers, so you don’t have to remember everything you need to do

AI tools that help with non-clinical physician roles like research

AI assistants that help with personal life tasks

One of the really exciting parts of AI related to cognitive load is the ability to quantify the many cognitively demanding tasks a physician performs.

Promising ways to use AI to quantify physician cognitive load include:

Time spent in the EHR during work and non-work hours

Hopefully eventually also on the phone and coordinating care in other ways

Time motion and eye movement analysis

Quantifying number of types of interruptions

Hard stop, passive, interruptive

In the future, there will hopefully be tools that can predict and quantify cognitive load based on a physician’s schedule and help balance it. When I was running the pain clinic in town, for example, I saw all the new patients so my schedule always had a much higher cognitive load than when I saw a mix of new and follow up palliative care patients.

I think many of us intuitively build our lives around a cognitive load that is do-able for us, and when that load is overwhelmed we naturally start to exhibit symptoms of burnout and even depression. Metacognition and awareness of the high “resting state” of the physician cognitive load may help physicians build systems in their personal and professional lives to bring that load to a level that is reasonable. Hopefully AI can help bring some of those elements to the forefront and quantify them to make them more visible to physicians and healthcare systems. And maybe it can even help flummoxed residents like me treat mild hypotension on their first days alone.