On April 22, 100 Kaiser nurses held a demonstration in San Francisco with slogans like “AI has to go!” Nurses quoted by the San Francisco Chronicle cited concerns about nurses being replaced by AI and lack of clinician involvement in deployment of AI tools.

Source: SF Chronicle

I totally agree with the importance of clinician involvement, though I’m somewhat perplexed by their slogans and other statements like “AI has to go”, which I have trouble thinking is anything other than reductive and simplistic.

However, the nurses’ concerns about how AI is used and deployed goes to a deeper issue about AI governance in healthcare: it’s moving much more slowly than the technology itself.

Policy? What policy?

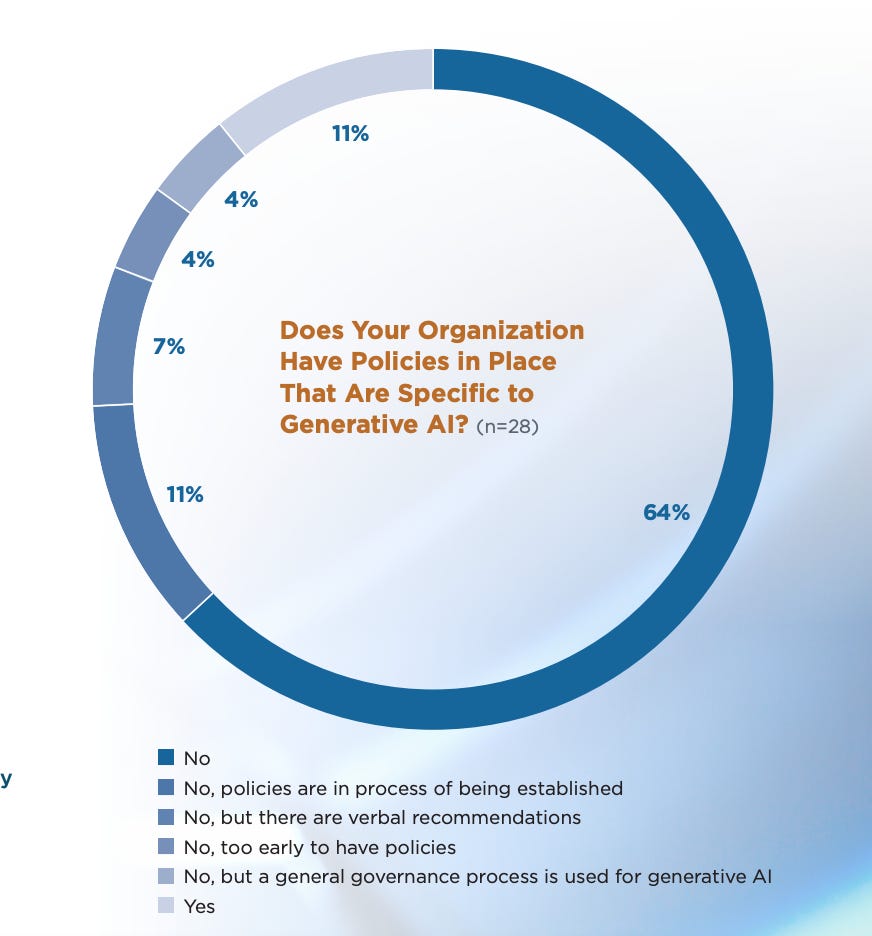

Only 16% of health systems have an AI-specific governance policy, and only 11% have a generative AI-specific policy, according to a recent survey by the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Center for Connected Medicine (CCM) and KLAS, a survey firm.

This survey had some other good nuggets in it, like the implication that a health system leads its AI implementation as it is to have the Chief Informatics Officer or Chief Clinical Officer.

The takeaway here is that “AI” touches many parts of the hospital, and there’s often no clear role that should assume responsibility. The fact that any legal team member is leading AI deployment points to the emphasis on AI governance and appropriate use of the technology.

Keep in mind that only 34 health centers responded to the survey and respondents were overwhelmingly non-medical executives; only 6 of the 35 who responded were CMIOs. Furthermore, AI policies could span a spectrum of thoroughness, usefulness, and appropriateness. I’d guess that some health systems’ existing policies that are not specific to AI may be better than some AI-specific policies. This survey was done in October and November (though published a few weeks ago) and some health systems may have adopted AI policies in the interim.

Health system policy development is not designed to respond to rapid tech innovation

We’ve established that front-line workers like nurses are concerned about AI governance issues and that health systems have been slow to adopt AI governance policies.

It seems blatantly obvious that health systems need to create these new policies; however, having served on several Medical Executive Committees and written several health system policies, they require many meetings with many stakeholders over many weeks and months. I’m sure many of you have reviewed policies that you thought were the most boring, slam-dunk writing you had ever done, only to have others think of implications or stakeholders that needed to be reviewed before it went to committee. I once made minor changes to a policy on pre-operative guidelines that took more than six months to get consensus on.

If writing a policy about a standard part of medical care is challenging, you can imagine the implications for the difficulty in writing AI policies. The culture of health system policy creation is basically the direct opposite of the “fail fast, fail forward” tech dogma. It’s not a surprise, then, that health systems don’t have clear policies in place yet. The logistical challenges of creating a policy for technology of unclear future use with possible implications in every department make it really hard to move quickly.

Two additional factors in moving healthcare AI governance forward are:

A lack of in-house expertise

The lack of clarity on a standard approach to healthcare AI

Lack of in-house expertise

I’ve met literally hundreds of smart, motivated physicians who are taking coding classes after long days in clinic to educate themselves about AI. They and the hard-working CMIOs and CMOs will lead the way for clinical AI use and implementation. Still, the number of physicians who are knowledgeable about AI is much lower than it needs to be, and the same is true of leaders throughout the hospital including nursing, allied health, and administration. As long as AI is a black box, the default for moving forward will be inertia.

Lack of clarity for a standard approach to healthcare AI

Thus far, there’s no government body or respected organization that has produced sample policies for AI, or even a set of recommendations or guidelines.

The good news is that smart people are thinking about this.

The Center for Healthcare AI and others have been way ahead of the curve in healthcare AI governance, thinking through these issues in the dark ages of the 2010s, and they proposed a healthcare AI model card back in 2020.

In March of this year, they joined with Microsoft to create the Trustworthy and Responsible AI Network, or TRAIN. Its members include Stanford, UCHealth, Boston Children’s, MGH, Hopkins, Mayo, and other big healthcare systems. Their industry partners other than Microsoft are Amazon, CVS Health, and Google.

Their goal is to:

“Develop “guidelines and guardrails” to drive high-quality health care by promoting the adoption of credible, fair and transparent health AI systems.”

Their approach is to:

Identify areas of interest and use cases

Develop core principles

Develop evaluation criteria

Produce implementation guides

https://www.coalitionforhealthai.org/our-plan

This is great and important work, but does not lend itself to being particularly fast or responsive to technological innovation.

Similarly, the AI Executive Order gave the Department of Health and Human Services until October 2024 to “create a comprehensive plan for assessing AI before it goes to market, and monitoring performance and quality once the technology is actually in use.” That seems like a fantastic idea and also incredibly hard to do in a detailed, meaningful way. There are working groups about “drugs and devices, research and discovery, critical infrastructure, biosecurity, public health, healthcare and human services, internal operations, and ethics and responsibility”. So only one eighth of this effort (healthcare and human services) is actually focused on patient care.

Interestingly, another Executive Order signed in February 2024 focused on keeping Americans’ sensitive data, including personal health data, out of the hands of “countries of concern that threaten U.S. national security and foreign policy”. It’s safe to say that most health systems have not considered threats to US national security while creating their data protection policies; the considerations for AI governance policies are becoming simultaneously more technically deep and conceptually broad.

Summary

The Kaiser nurses are right that we need to have a good governance plan for healthcare AI. Though I disagree with much of their message, it’s a positive sign that frontline workers are advocating for safe and effective use of AI in healthcare. One of my favorite parts of being a physician is working with people who all share the common goal of providing excellent care to our patients. Educating ourselves and our colleagues about the best and most ethical ways to use this new technology, and putting policies in place that reflect those values, will ensure that AI is used in a way we can all agree on.